Understanding The Shoulder Joint

Click here to see a video version of this article (I recommend reading first and then watching).

If you like to lift weights, you've probably trained muscles that cross your shoulder joint at some point.

But you've also probably experienced pain in your shoulders while trying to do that.

Why might that be?

While we can't ever come to a single, certain answer to this question, I believe that our chances of experiencing pain in the gym are substantially lower when we gain an understanding of how the shoulder is structured and how it's naturally meant to move.

Bony Anatomy

The shoulder joint is the most mobile in the body.

To understand why this is, we need to look at the bones that comprise it:

- The clavicle

- The scapula

- The humerus

- The ribcage

The Clavicle

The clavicle is a thin, s-shaped bone that is the shoulder girdle's ONLY true joint connection to the rest of the body.

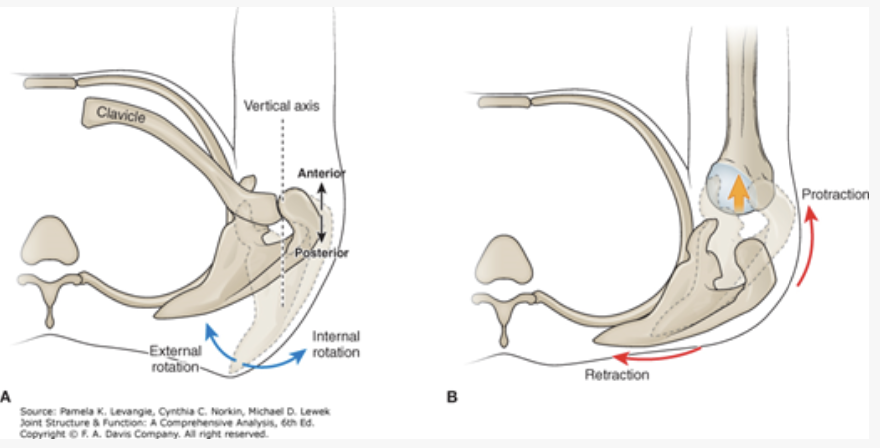

The clavicle can pivot upward, downward, forward, backward, and rotate.

Retraction = pivot backward

Protraction = pivot forward

Elevation = pivot upward

Depression = pivot downward

Posterior rotation = spin backward

image credit: https://clinicalgate.com/shoulder-complex/

The clavicle sets the stage for motion of the humerus (upper arm) and scapula.

The Scapula

The scapula is a triangle-shaped bone that sits on the back of the ribcage.

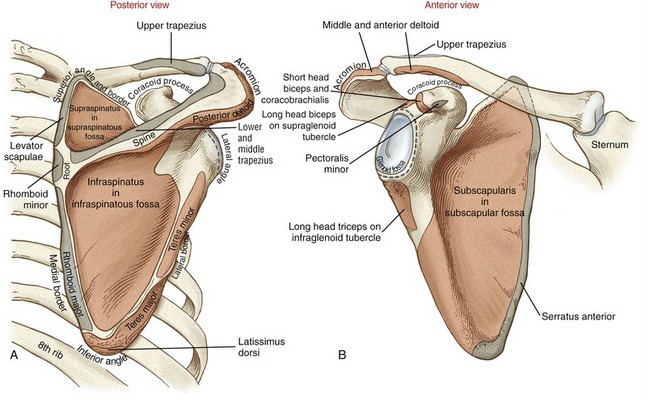

image credit: https://clinicalgate.com/shoulder-complex/

The scapula is highly mobile, much like the clavicle, and provides the 'socket' which the upper arm sits in.

The scapula is what provides the 'tee' for the 'golf ball' (upper arm) to safely sit within (see above: that circular thing that's white and smooth).

The scapula can slide upward, downward, forward, backward, and can rotate upward and downward.

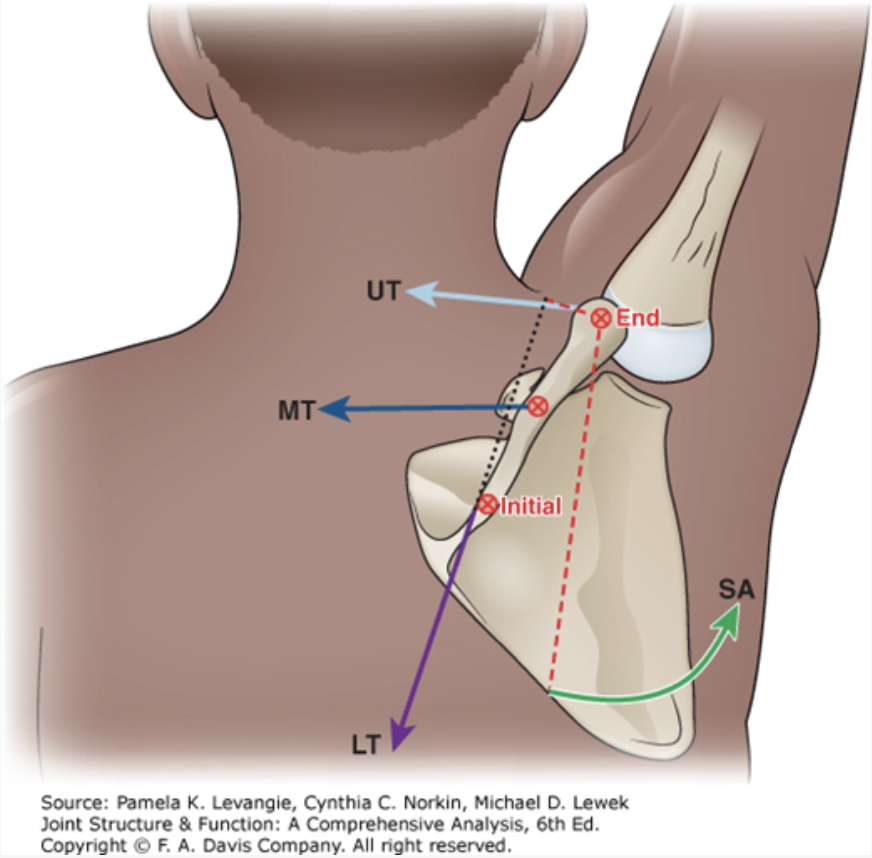

image credit: https://clinicalgate.com/shoulder-complex/

Retraction = motion backward toward the spine

Protraction = motion forward away from the spine

Elevation = motion upward

Depression = motion downward

Upward rotation = motion of the socket upward toward the sky

Downward rotation = motion of the socket downward toward the ground

The Humerus

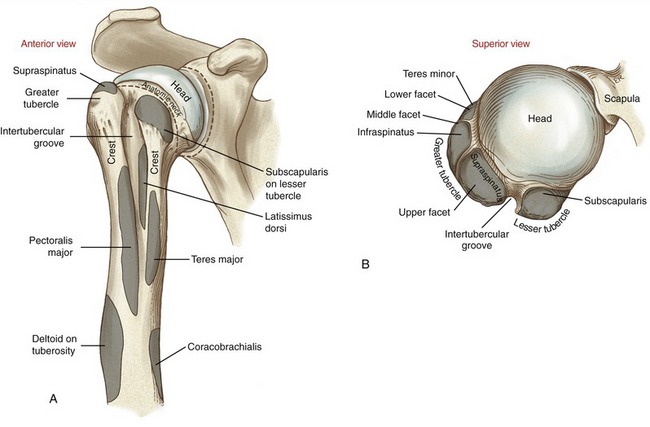

The humerus is the upper arm bone where the the extremity attaches to the rest of the body.

image credit: https://clinicalgate.com/shoulder-complex/

The above image shows the top half humerus (that long, stick-looking thing) where it converges into a ball (remember that 'golf ball in a tee' thing) and attaches into the socket of the scapula.

The humerus can move in any direction, up to structural limits.

Simple deconstruction of these motions:

Adduction = motion toward the midline of the body

Abduction = motion away from midline of the body

Internal Rotation (also called medial rotation) = spinning toward the midline of the body

External Rotation (also called lateral rotation) = spinning away from the midline of the body

Extension = motion of the arm downward/backward behind the body

Flexion = motion of the arm upward/forward in front of the body

The Ribcage

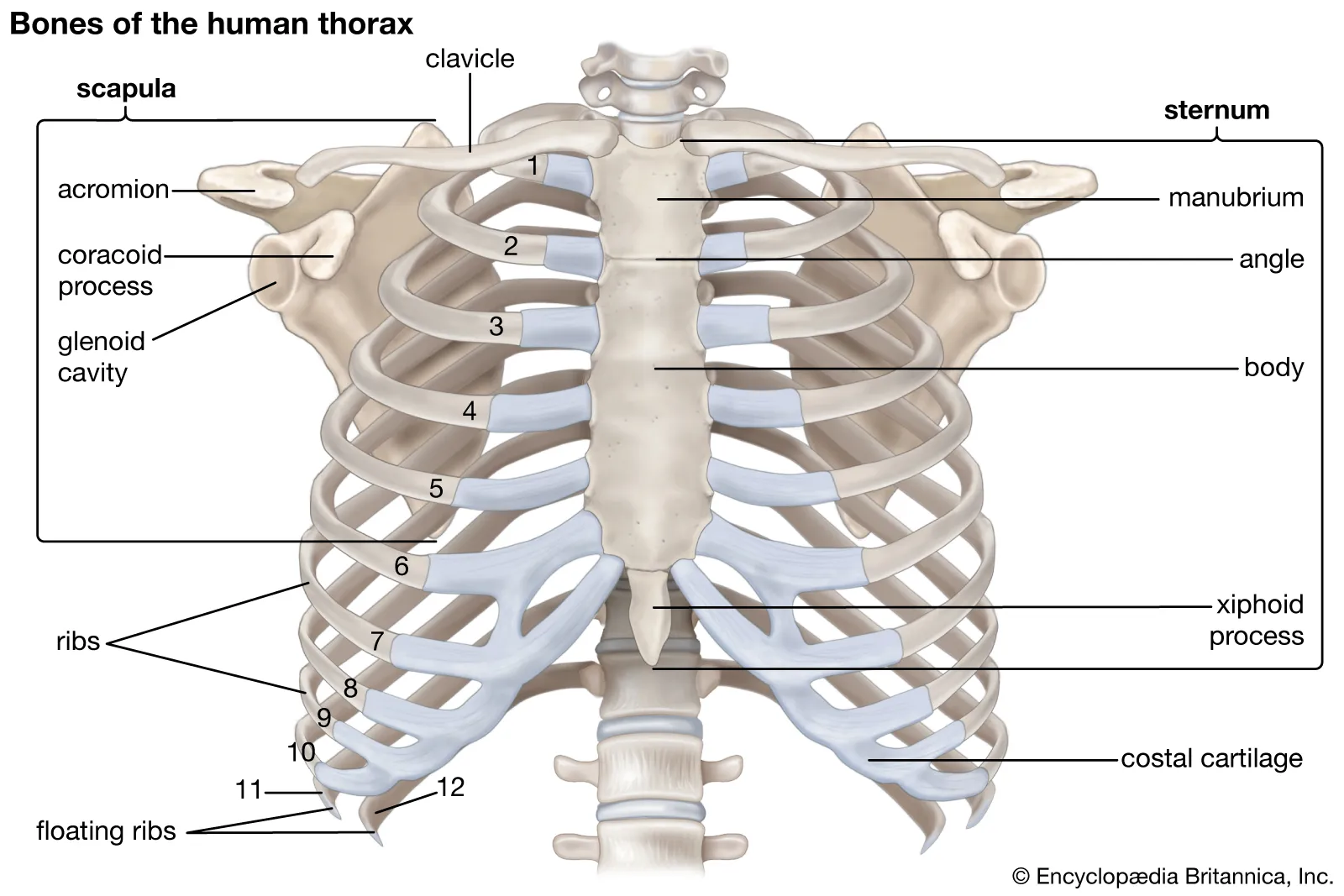

The ribcage is the bedrock of the shoulder girdle.

The scapula, clavicle and humerus all sit atop the ribcage. This means that any motion of the shoulder girdle must accommodate for the shape of the ribs beneath it.

source: https://www.britannica.com/science/rib-cage

This may seem less important than understanding the structure of the other bones, but I assure you, it's not.

If anything, the structure of an individual's ribcage is what the other bones rely on to create and accommodate motion.

Here's an example of what I mean when I say "shoulder girdle must accommodate for the shape of the ribs beneath it":

The implication here?

That no scapular motion can occur like bones in the rest of our body.

This is to say that, any time there is motion of the scapula, there is motion in more than one way.

If the scapula slides upward into elevation (see above image), it also must tip forward, and vise-versa for depression.

Bringing it All Together

Talking about individual joint actions and bones is useful.

In reality, though, all of these structures and actions are paired and inseparable by nature.

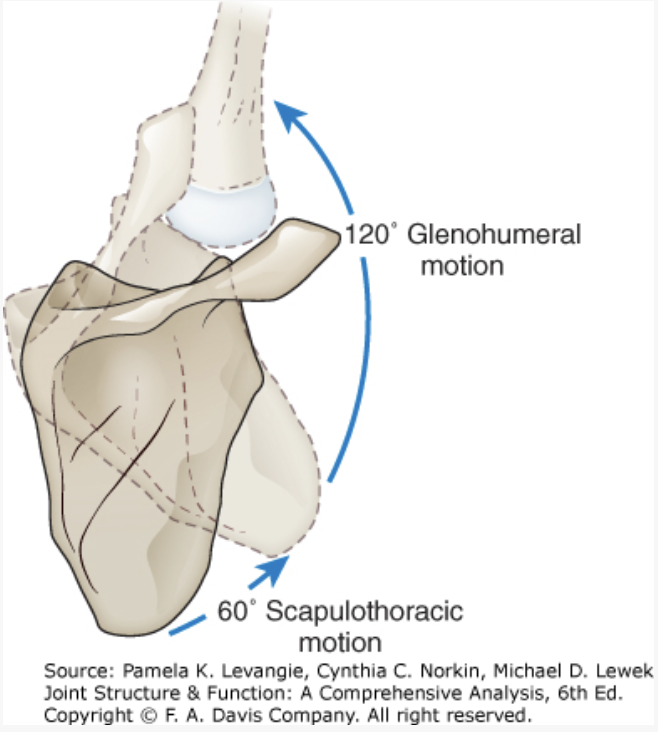

When we raise the arm forward or up and outward to the side, the scapula, clavicle, and humerus all need to pivot on top of the ribcage in sync:

This same 'in-sync' motion also occurs when we reach the arm forward and backward, only now with different kinds of scapular, clavicular and humeral movement:

The above photo shows a top-down view of what someone who is reaching forward and backward would look like.

Application to Resistance Training

In order to understand how to load these joint actions appropriately, we need to understand the directions of motion that occur when we move.

For example, when performing a lateral raise, I need to understand the direction of motion of my bones so that I can load myself in the opposite direction.

Much of the discomfort people experience in the gym - in my experience - comes from loading our bodies in directions that we are not attempting to move.

This creates a greater challenge for the brain to coordinate - but not the kind of challenge we're looking for when lifting.

In future articles, I'll cover how you can apply this knowledge of structure and basic joint actions to loading yourself in a way that's appropriate for the goal.