The Elbow Pain Solution

Elbow pain is so common, the average lifter believes it's simply par for the course of training.

But it doesn't need to be this way

And what you think is "triceps tendonitis" might actually be "poor exercise selection and execution".

Here's what you'll understand after you finish this post:

- A simple model of pain and how to handle it.

- 5 key principles to implement into your training TODAY to make an immediate and long-term difference in your elbow pain (and muscle growth potential).

- Includes exercise diagrams & my personal recommendation for biceps and triceps training.

How To Understand Pain

Pain is a complex phenomenon - but in my estimation, a simple analogy suffices to understand pain.

Imagine you have a bucket.

Each time you lift, you fill up your bucket with water.

The bucket represents your capacity to handle stress (i.e., stimulus).

The water represents the stress itself.

Fill the bucket without overflow - you've got positive adaptation in your future.

Overflow the bucket instead - pain signals occur (or worse, injury).

These pain signals exist for good reason - to alert you that you've exceeded your body's current capacity to handle imposed stress.

Each muscle and joint in our body has its own "stress bucket", which can grow or shrink depending on circumstance.

If you're already in pain, or you've incurred prior injury, your bucket is likely smaller than it could be - and therefore your capacity to fill your bucket is limited.

My hypothesis for solving elbow pain (and principally any other kind of physical pain): first remove the most obvious insults to injury - remove excess water from the bucket - then regain the capacity to build a bigger bucket (to eventually fill more wisely moving forward).

Now, let's dive into specific principles to maximize the chances of stressing muscle more than the joints they support.

Principle #1 - Align Resistance With Elbow Path

The elbow is a hinge joint - meaning that it can only move in a single path, like how a wrench moves around a bolt:

When you use a wrench, you move the wrench in a single path - you don't move the wrench upward and downward or twist it side-to-side - you move it in the direction which allows a bolt only to tighten or loosen.

The same should apply to loading our elbow joint when training the biceps and triceps:

- When training triceps, we should use a resistance that only "wants" to bend the elbow.

- When training biceps, we should use a resistance that only "wants" to straighten the elbow.

- Side-side or twisting forces will load only the connective tissues of the elbow, not the biceps or triceps.

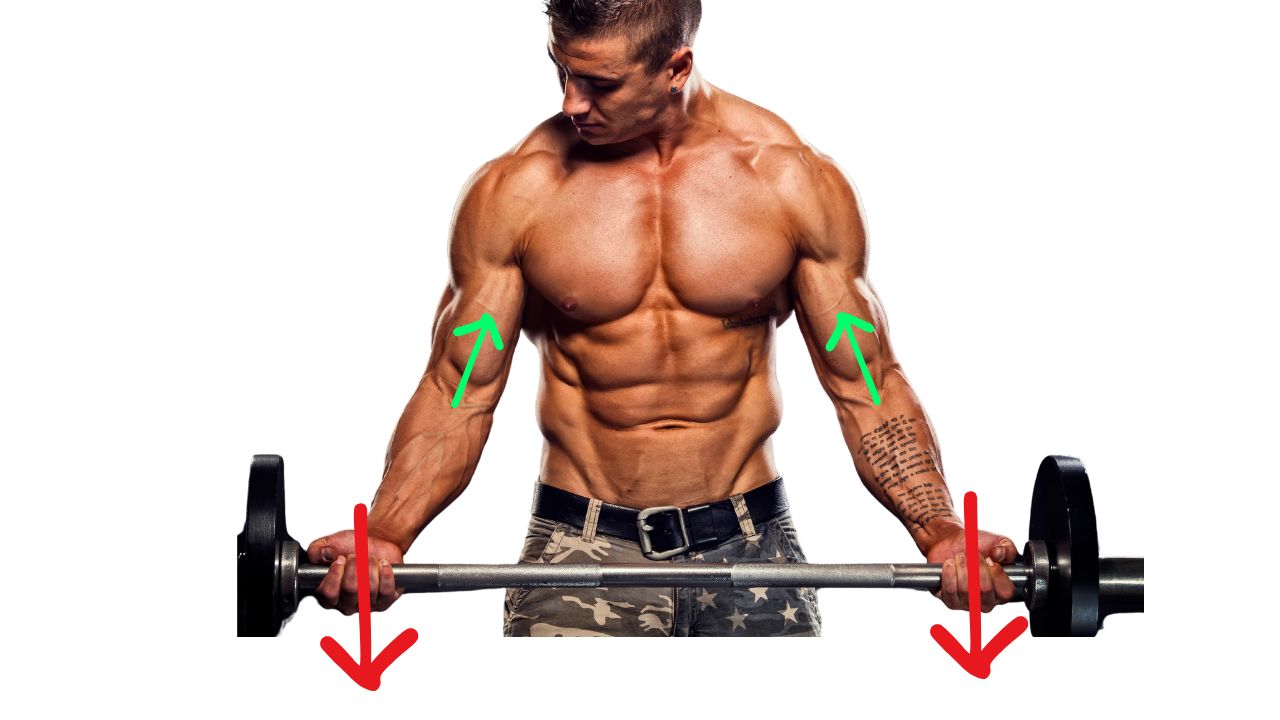

Let's inspect the traditional barbell curl. Note the direction of resistance (red) which the barbell imposes on the hands in this position:

Now look at the direction that the elbows would naturally move green) if unaffected by the constraint of the bar:

Note how the red (resistance) and green (elbow path) arrows do not align parallel.

This implies that we're loading the elbow - or turning the bolt - in a direction that it does not actually move.

Recall our bucket analogy: in this instance, our elbow joint's bucket is being filled disproportionately to our biceps bucket.

Of course, this is not an immediate sentence to pain.

But why fill up our elbow joint bucket more than necessary if our goals are solely to train elbow muscles?

By definition, we're already stressing the elbow joint plenty (filling up our elbow bucket) by virtue of the fact we're training arms.

Any time one performs a biceps or triceps exercise, the elbow joint bucket fills - and in most cases, we need not fill this bucket more than this.

I'll give another example, then talk about solutions.

Below is a traditional triceps skull-crusher. Note the direction the bar wants to move the hands (red) and the direction the elbow would naturally move (green) if unconstrained by the bar:

Again - we ideally want these arrows align paralell to load the elbows in the direction they move.

Put differently: we want parallel arrows so our elbow bucket fills as little as possible relative to our triceps bucket.

Here are two alternatives to making such changes in the case of a biceps curl and triceps extension:

Note how, in either instance, the direction of the resistance (red) and the direction of elbow motion (green) are now parallel.

We are no longer loading the elbow in a side-to-side or "twisting" direction.

Put another way: we're now disproportionatley filling the biceps and triceps buckets compared to the elbow joint bucket.

Principle #2 - Prioritize Free-Moving Implements

Something I failed to mention earlier: the elbow isn't just a joint...it's technically a complex of three distinct joints.

And many perceived "elbow" problems may not directly relate to the wrench-like joint described earlier (technically what is known as the humeroulnar joint).

The two other joints, known as the humeroradial and proximal radio-ulnar joints (see left image below), are what allow for the forearm to twist (see right image below):

If your pain is on the outside of your elbow, the solution may have more to do with creating freedom for the forearms to rotate (think "jazz hands").

Think of it this way: the "joint bucket" that may overflow might not be the wrenchlike joint, but instead the one that twists.

In practice, implements which allow the forearms to rotate freely - like dumbbells, individual cable handles, and some machines - will provide more freedom for you to adjust grip so that every exercise can be performed in a more individualized manner.

Fixed implements - barbells, EZ bars, and some machines - constrain the hands so the forearms can't rotate as freely.

Fixed implements are not inherently bad to use - but if you're sensitive to elbow-related problems, it is wise to err on the side of free-moving grips over fixed grips when possible.

Why I think this happens and why it matters: if you're constantly using the same grips (i.e, all your arm, back and chest training is done with fixed implements) with the same restriction to motion, you might simply be stressing the same connective tissues repeatedly (without appropriate time for them to recover between sessions).

In essence, free-moving implements allow you to distribute stress into buckets that are either bigger or those which haven't been filled very much - whereas fixed implements repeatedly funnel water into the same bucket.

Principle #3 - Adjust Range Of Motion

It may seem obvious, but if ONLY one small portion of an exercise is bothering you, just avoid that one portion!

Think of it this way: your bucket size for one specific joint position may be different from every other joint position.

Just imagine how many stress buckets you have...

If only the TOP position of a triceps extension is bothering your elbow - like when you're at the top of a rope triceps push-down - perhaps decrease the range a little bit so you're not bending your elbow as much.

If you're doing biceps curls and ONLY the bottom position - when your elbows are straight - is bothering you, it may be a good idea to simply avoid that portion of the range for a couple of weeks.

Avoiding these positions temporarily isn't a bad thing, and it doesn't mean you're damaged - you can eventually plan to load these joint positions again, once your buckets for those positions are less filled and when your buckets have grown bigger over time.

Remember this: buckets grow slowly, but it's really easy to add a lot of water to them (and fast).

So, err on the side of slow rather than fast when it comes to adding more stress back into your buckets.

Principle #4 - Adjust Loading Challenge

Every exercise one performs has a unique loading challenge - which is to say that every exercise is heavier at specific portions of the movement and lighter in others.

Take the typical standing dumbbell curl, for example: it is heavier in the top and lighter at the bottom (the red line below represents a moment arm, which you can think of as proportional to how heavy something is):

This may be a good option for someone who experiences elbow pain in more elbow-straightened positions, because the elbow is less loaded when the elbow is more straight.

However, in a circumstance wherein the more elbow-bent position is painful, it may help to choose an exercise with an opposite challenge.

In other words: it may be more helpful for someone who has pain in the elbow-bent position to choose an exercise where the bottom of the motion (where the elbow is straighter) is proportionately heavier than the top, like this (where the moment arm is now indicated in green and resistance in red):

Although the implement itself hasn't changed between variations (dumbbells apply the load in both), simply changing the orientation of one's body relative to the direction of gravity can dramatically shift where an exercise is heavy and light.

For the person who has elbow pain in straighter elbow positions, the first option will likely be a better choice - while the inverse is true of someone who has pain in more bent-elbow positions.

One can apply this strategy to triceps extensions as well - simply changing where the triceps (and the elbow joint) are loaded most can account for the relative bucket sizes in either position.

For instance, imagine elbow pain is present toward more straight elbow positions, but not more bent positions. A setup like this (where the red represents a cable) may be more appropriate, where the more bent position is heavier than the more straightened position (moment arm again in green):

However in another circumstance, where the more elbow-bent position is more painful, it may be beneifical to reverse where the exericse is heavy and light (imagine I step away from the cable now so that it's in front of instead of above me):

Simply adjusting where an exercise is heavy and light may give you enough freedom to be able to thoroughly train where pain isn't present and to avoid aggravation where pain is present.

In other words: simply by changing your relationship to the resistance of an exercise allows you to alter how much each position's stress bucket gets filled on every rep.

Principle #5 - Sometimes You Need a Break

We can't rule out the possibility that sometimes our stress buckets for particular joints and/or muscles are so overflowed that the only way to return to baseline is to give our bodies time to reset.

There are legitimate reasons to believe this might be the case for you, especially if you've applied all the adjustment principles above to no avail.

Keep in mind that other motions - particularly presses in the case of triceps-related pain and pull-downs in the case of biceps-related pain - also add to the bucket of stress which is already overflowed.

So while I don't recommend you stop training entirely, you should err on the side of taking away more stress than is necessary - you can always add more stress later, but if you do too much now, you may delay your ability to recover in a way that doesn't move the needle of positive adaptation.

Below is a video of me talking through these principles with cable and dumbbell examples.

To view it, you must be a paying subscriber of the Modern Meathead Membership.

With a membership, you'll get instant access to all paid content as well as a library of exclusive long-form lectures (currently totaling ~20 hours).

You can start an 100% risk-free 7-day trial by signing up below.

-Ben

The Modern Meathead Newsletter

Giving you brain gains every week (so you can make real gains in the gym)