An Introduction To The Shoulder

In my experience, when one better understands the structure and function of a joint...

- One's chance of experiencing pain in the gym tends to be lower.

- One's liklihood of targeting specific muscles with precision is substantially higher.

By the end of this post, you'll learn the bedrock of this understanding: the basic anatomy and function of the shoulder complex. You'll also learn the jargon (the words people use to sound smart), which I've translated into layman's terms.

Bony Anatomy

The shoulder joint is the most mobile in the body.

To understand why this is, we need to look at the bones that comprise it:

- The clavicle (collar bone)

- The scapula (shoulder blade)

- The humerus (upper arm)

- The ribcage (you know that one...)

The Clavicle

The clavicle is a thin, s-shaped bone

Fun fact: from the side, it looks like a spine!

The clavicle serves as the shoulder girdle's ONLY direct joint connection to the rest of the body, where it attaches to the sternum:

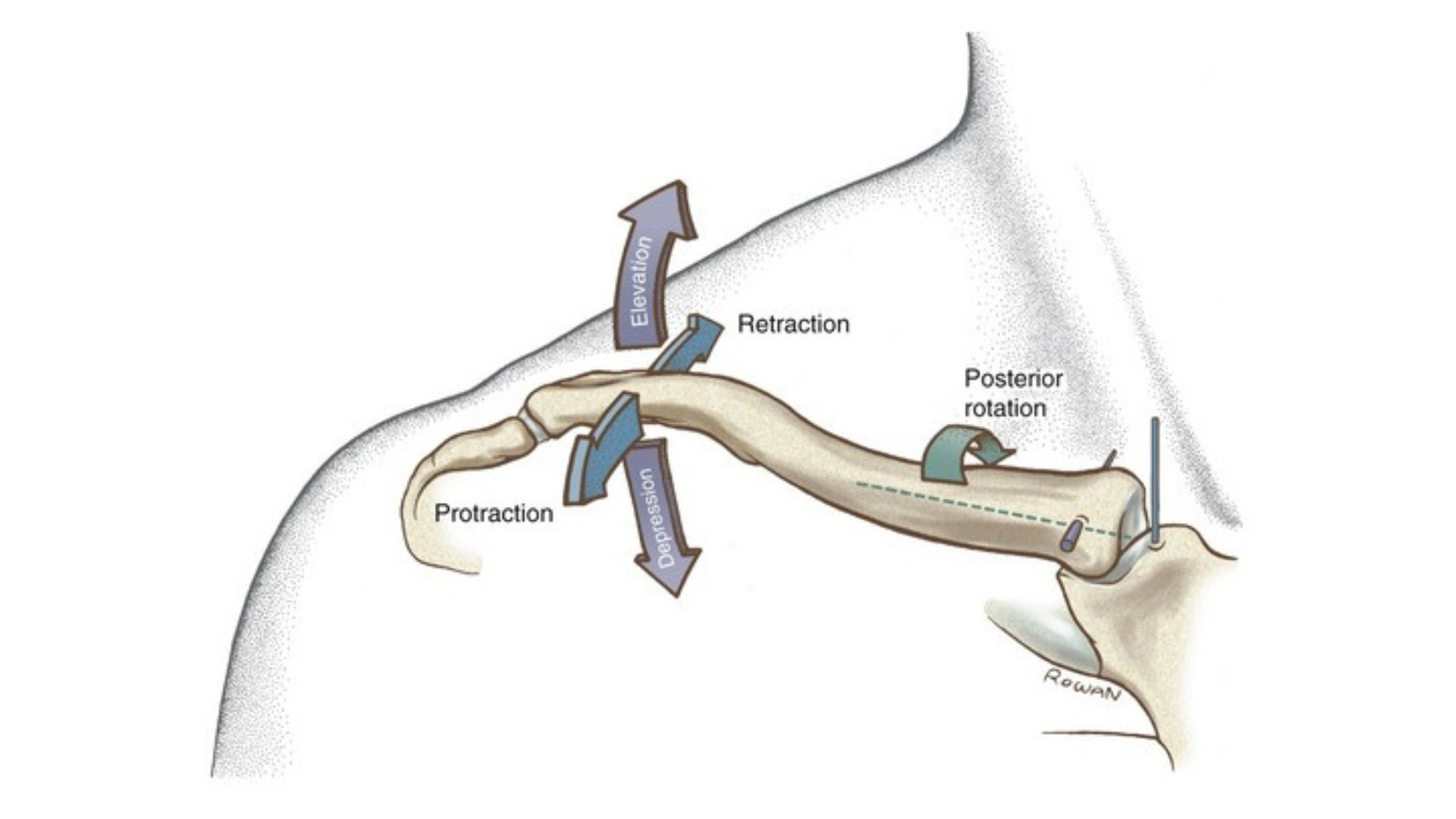

The clavicle can pivot upward, downward, forward, backward, and spin (look at the words below and the arrows shown above).

- Retraction = pivot backward

- Protraction = pivot forward

- Elevation = pivot upward

- Depression = pivot downward

- Posterior rotation = spin backward

The clavicle sets the stage for motion of the humerus (upper arm) and scapula (shoulder blade).

The Scapula

The scapula is a triangle-shaped bone that sits on the back of the ribcage.

Image Source: Complete Anatomy

The scapula is highly mobile, much like the clavicle, and provides the socket that the upper arm connects to.

In other words, the scapula provides the "tee" (socket) for the "golf ball" (upper arm) to safely sit within (see above: the socket, also known as the glenoid).

The scapula can slide upward, downward, forward, backward, and can rotate upward and downward.

- Retraction = motion toward the spine

- Protraction = motionaway from the spine

- Elevation = motion upward

- Depression = motion downward

- Upward rotation = motion of the socket upward toward the sky

- Downward rotation = motion of the socket downward toward the ground

Important note: any motion of the shoulder blade is paired directly with the clavicle.

For example, when the scapula elevates and upwardly rotates - like when you raise your arm above head - the clavicle pivots upward, too.

The Humerus

The humerus is the upper arm bone.

Image Source: Complete Anatomy

The above image shows a left humerus (which converges into a ball or "head" - remember that "golf ball in a tee" thing) and how it connects to the socket of the scapula.

Collectively, this "ball and socket" joint is known as the glenohumeral joint, which is what most people mean by "shoulder joint".

The humerus can move in any direction, up to structural limits:

Image Source: SequenceWiz

Simple deconstruction of these motions:

- Adduction = arm motion toward the midline of the body.

- Abduction = arm motion away from midline of the body.

- Internal Rotation (also called medial rotation) = arm spinning toward the midline of the body.

- External Rotation (also called lateral rotation) = arm spinning away from the midline of the body.

- Extension = motion of the arm downward/backward behind the body.

- Flexion = motion of the arm upward/forward in front of the body.

The Ribcage

The ribcage is the bedrock of the shoulder girdle.

The scapula, clavicle and humerus all sit atop the ribcage. This means that any motion of the shoulder girdle must accommodate for the shape of the ribs beneath it.

Image Source: Cleveland Clinic

This may seem less important than understanding the structure of the other bones, but I assure you that it's not.

The structure of an individual's ribcage is what the other bones rely on to organize motion.

Here's an example of what I mean when I say "the shoulder girdle must accommodate for the shape of the ribs beneath it":

Image Source: Joint Structure & Function, 6th Edition

The implication here?

No scapular motion can occur like bones in the rest of our body.

This is to say that, any time there is motion of the scapula, are are multiple different kinds of rotation occuring simultanously.

If the scapula slides upward into elevation (see above image), it also must tip forward (and vise-versa for depression).

Luckily, our brain does a great job of coordinating this motion - because if we were tasked to consciously need to coordinate it...we'd probably be in trouble.

Bringing it All Together

Talking about individual joint actions and bones is useful.

In reality, though, all of these structures and actions are inseparable by nature.

When we raise the arm forward or up and outward to the side, the scapula, clavicle, and humerus all need to pivot on top of the ribcage in sync:

Image Source: Joint Structure & Function, 6th Edition

This same "in-sync" motion occurs when we reach the arm forward and backward, only now with different kinds of scapular, clavicular and humeral movement:

Image Source: Joint Structure & Function, 6th Edition

The above photo shows a top-down view of what someone who is reaching forward and backward would look like.

An Important Caveat

While understanding jargon is important, in application, one must remember that language is limiting in terms of how accurately it describes motion in every context.

Concrete example: recall the term for motion of the arm away from midline of the body: abduction.

This works well in describing the bottom half of an overhead raise, like this:

Image Source: Stanford Medicine

However, when we continue to raise the arm upward from 90º, the arm actually moves inward toward midline (technically adduction), rather than away from midline:

Image Source: Stanford Medicine

This does not mean that the term "abduction" is incorrect or lacks utility (these are exceptions), but rather that there are limitations to the language we use in many contexts (just like in any other field of study).

It is therefore useful to remember that these terms are limited in their application and that the primary focus should be on the joint motions occuring rather than the specific language we've made universal by necessity.

Application to Lifting

In order to understand how to train specific muscles, we must first recognize the bony motion such muscles create upon contraction.

For example, if my goal is to target the side delts, I must first identify that the side delts create abduction of the glenohumeral joint and that I must load the opposing direction accordingly (with a dumbbell, cable, etc.).

Failed exercises - those which do not accomplish the desired goal - most often come from load-joint mismatch, wherein the load one uses does not actually oppose the target muscle's joint function.

Now that you've got a basline understanding the shoulder complex, you can begin to assess individual muscles, their function, and how to train them accordingly.

Detailed Video Guides

Reading about this stuff is great, but a full understanding requires visual representation of the concepts.

Below, I've uploaded 5 different videos - all on shoulder anatomy - taken directly from my advanced biomechanics course:

- Two lectures on the shoulder complex

- A lecture on the clavicle

- A lecture on the scapula

- A lecture on the humerus

All with detailed demonstrations using my full-size skeleton model (Frank).

To view them (as well as 50 other subscriber-only lectures) you can start a 7-day risk-free trial to the Modern Meathead Membership below or at this link.

This is also a great way to support all of my free content now and in the future.

View the lectures below:

The Modern Meathead Newsletter

Giving you brain gains every week (so you can make real gains in the gym)