Shoulder Blades Back And Down Is Killing Your Gains

For years, I swore by one cue above all others: "shoulder blades back and down" - it was gospel for me as it is now for thousands of lifters.

But today I'm going to share why I stopped using this cue (not entirely, but mostly) and why I think you should consider doing the same.

So, if you're a "shoulders back and down" enthusiast - and you believe you've seen success from it - this article will be highly valuable to you, because I think you're going to change your mind about some very important anatomical truths.

This Might Surprise You

This will undoubtedly be shocking to many of you who are "shoulders back and down" zealots: when the shoulder blades move backward - which is to say that when shoulder retraction occurs - they simultaneously move upward, not downward.

This is something people are deeply confused about and most often refuse to acknowledge when shown the irrefutable facts of the situation.

We can debunk this "back and down" thing from two perspectives: the bony and the muscular.

The Bony Reality

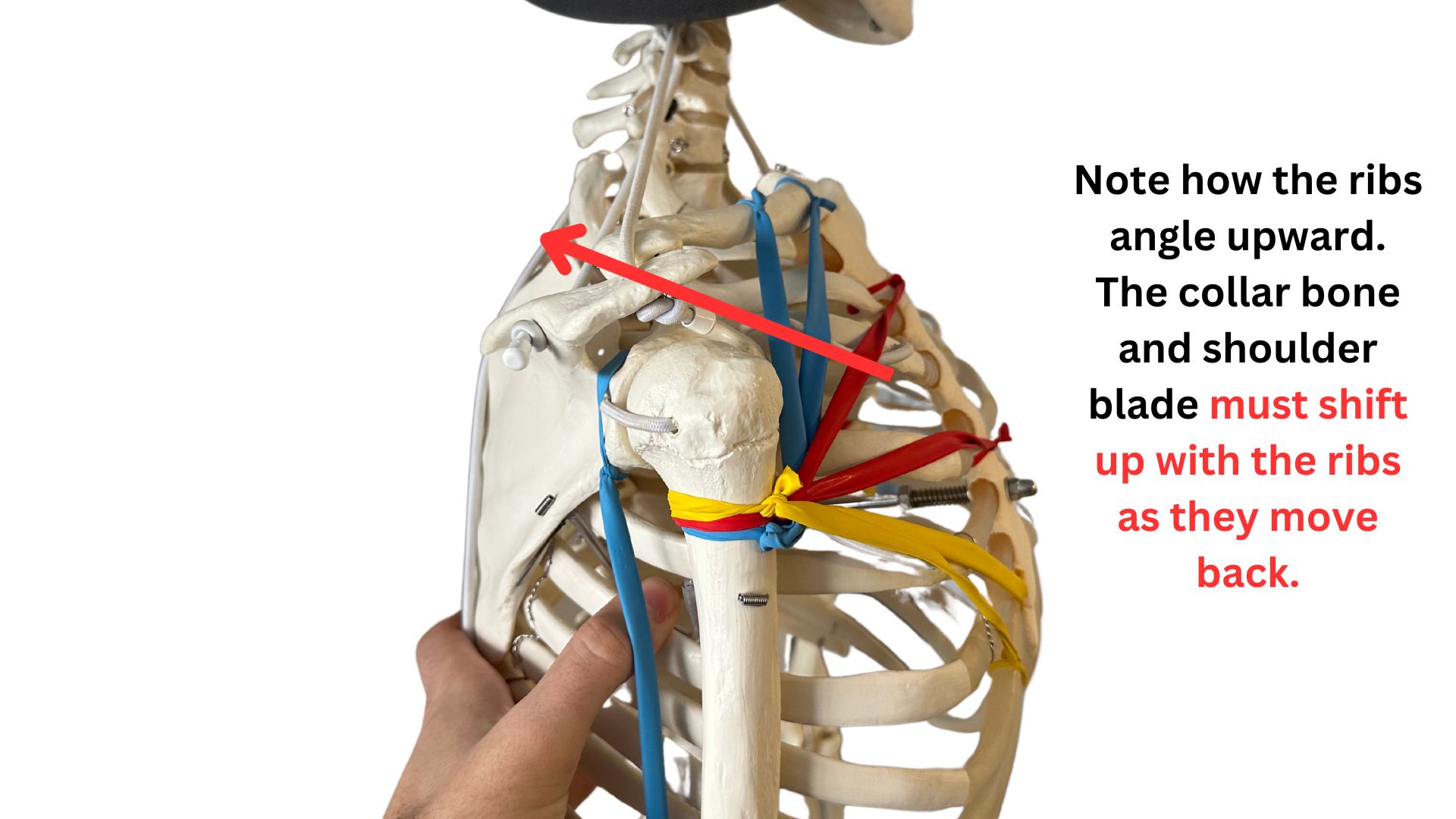

When you pinch your shoulder blades together, your entire shoulder girdle, including your collar bone, also needs to move backward.

The shoulder blade and collar bone both sit atop the ribcage, which all of you are likely familiar with.

The ribcage functions as the foundation for the shoulder girdle's motion.

And you can think of the ribcage as the tracks upon which the train (the shoulder bones) sit; wherever the shoulder bones move, they must move in accordance with the structure beneath them.

When looking at the shape of the ribcage, you'll notice it's shaped kind of like the top half of an egg. It's wider at the bottom and gets narrower toward the top:

What's this mean?

When the shoulder blades move backward (along with the collar bone and upper arm), they physically cannot move downward because the collar bone would have to move down through the ribcage to do so (there are contextual exceptions to this which we'll go over later).

Here's a visual of what I mean:

The Muscular Reality

The primary retractors of the shoulder girdle are the rhomboids and the middle traps. Here's what they look like:

Both the rhomboids and middle traps are powerful retractors, but the rhomboids tell the story more clearly: note how their fiber orientation is not angled downward, but rather upward from their attachment on the shoulder blade into the spine. This is because they pull the shoulder blades back and UP when creating full retraction of the shoulders.

The Cuing Problem

Understanding the anatomy and physics is great - but what's the problem with trying to pull the shoulder blades backward and downward?

Aside from the fact that we can't actually move our shoulder blades down and back at end-range retraction, this has muscular and joint consequences as well.

The shoulder, as many of you likely know, is the most mobile joint in the entire body (it's really a collection of 3 distinct joints).

This creates upsides and downsides insofar as function is concerned: we can move our shoulders a lot, but the shoulder is far less structurally supported compared to other joints like the hips and elbows.

What this means is that the shoulder relies on its mobility to create its structural support - the shoulder blade functions as the base of support upon which our upper arm can move.

Wherever the upper arm goes, therefore, the shoulder blade must also go - otherwise, our shoulder won't be supported in the way we need, especially when lifting heavy weights in the gym.

So the first and most obvious problem here: intentionally restricting shoulder blade motion is synonymous with an attempt to take away the structural support that the shoulder complex relies on to function.

The second (and perhaps less obvious problem) is the restriction to muscular contraction that this intent can create across a variety of contexts.

The Chest

The most common context in which "shoulder blades back and down" is applied is undoubtedly the bench press., which, ironically, is one of the main contexts in which I would not recommend this cue.

Why?

The pecs - specifically the middle (sternal) and lower (costal) portions of the pecs, are powerful shoulder protractors.

So, in addition to the role they play in "pushing" the bar off our chest in a bench press, they also pull the entire shoulder girdle - including the shoulder blade and collar bone - forward.

Attempting to fully restrict forward motion of the shoulder blades is synonymous with limiting chest contraction.

So Why Does It Work?

Many cues "work" not because of their anatomical or physical accuracy, but because of what these cues get us to do when we think of them.

This is the difference between literal and metaphorical truth: literal truths are those which are factually correct, while metaphorical truths aren't, but prove useful despite the facts.

In the context of a bench press, thinking about keeping the shoulder blades backward and downward is synonymous with creating spinal extension - which is to say that, "shoulders back and down" is another way to arch your back.

Arching your back on the bench press has several benefits for strength: it shortens the range of motion, allowing lifters to use more load. It also turns the press into more of a decline press, where the larger portions of the pecs (middle and lower) can contribute more effectively.

In addition, pulling the shoulder blades "downward" as you press might create an unconscious movement of the arms closer inward toward the body, which also gives the middle and lower chest more leverage to press the bar up and off of the chest.

My argument here is that we need not utilize cues that are factually incorrect but functionally useful; instead, we should recognize the physical realities of the situation, and simply learn to position ourselves in the strongest positions possible (if the goal is to bench press the most weight possible) - all the while allowing the shoulder blades to slide as they're meant to.

What About The Contextual Exceptions?

I mentioned earlier that there are contextual exceptions to the whole "back and down" thing.

And what I meant by that is that there are certain positions from which our shoulders CAN move backward and downward, but that these positions are often not the circumstances in which people are using these cues.

For example, if my arm gets pulled upward and overhead - as in a lat pull-down - in the stretched position, my shoulders are positioned upward and forward.

As I pull downward, my shoulders will inevitably move backward and downward to some degree, but only because they're returning from a place in which they were positioned upward and forward.

When people cue "back and down" in a pull-down, it often makes sense - because the lats function to pull the shoulder blades back and down from an upward-and-forward position.

But in the context of a bench press, or really any other motion where the arms need to move behind the body, the opposite motions must occur for the reasons we've already discussed.

Ultimately, the cue is not the problem; rather, it is the context in which the cue is applied and the mistake in assuming that because something works that it must be anatomically and physically accurate, or that it should be used in every context possible.

-Ben

P.S - consider starting a 7-day free trial to my membership platform to receive brand new exclusive video content from me every week (plus other awesome stuff). Click here to see more details.

The Modern Meathead Newsletter

Giving you brain gains every week (so you can make real gains in the gym)

Responses