Blog

Break The Lifting Spell

Machines are better than free weights.

Wait...

or is it supposed to be the other way around?

I forget.

Have you heard these kinds of claims?

They've infested the fitness space for as long as I can remember.

Here's how people (usually) end up here:

1. An individual embarks on their lifting journey for the first time.

2. The individual (understandably) has no knowledge of what to do, so they ask others - presumably those who know what they're doing - for advice.

3. The "others" - whether knowledgeable or not - tell the beginner what exercises they should (often communicated as "need to") do.

4. The individual (understandably) likes some exercises more than others.

5. The individual (understandably) assumes there is something special (read as "mystical" and "magical") about the exercises they like.

If this story makes no sense to you, then you're lucky - you're likely someone who's been fortunate enough to learn from intelligent people.

I assume, however, that this story reso...

Why You Should Use The Smith Machine

I love using the smith machine.

If you asked the typical "if you could only have one piece of equipment" question, I'd probably say smith machine (functional trainer is a close second, for what it's worth).

Before I get into the reasons, let me get this out of the way...

The smith machine, like anything else you use in the gym, is a tool.

It has upsides and downsides.

There are trade-offs to everything.

But it is certainly NOT "non-functional" and it certainly does NOT "do all the work for you" as some anti-machine "educators" claim.

It is literally just a bunch of metal with a bar that falls toward the center of the earth.

So what do I love about the smith machine?

And why would I recommend including it in your program?

Reason #1 - you can do a bajillion different variations.

First and most obviously...

there's a TON of great exercises you can do on the smith machine.

The list is, practically speaking, endless.

- 2-leg squats

- Reverse lunges

- Split Squats

- RDL

- Bench

- I ...

How To Train Erectors

The bedrock of a hulking back is your erector group.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with this muscle group, it looks like this:

Having big, strong erectors - generally speaking - makes the spine more resilient.

These muscles are what allow you to pick heavy stuff up off the floor.

Pretty important task for daily life.

Training the erectors is fairly straightforward.

In fact, people who'd rather train their legs accidentally train erectors in many exercises (which, in multiple instances, is unavoidable).

Today, I'm going to show you how I like to (intentionally) target the erectors.

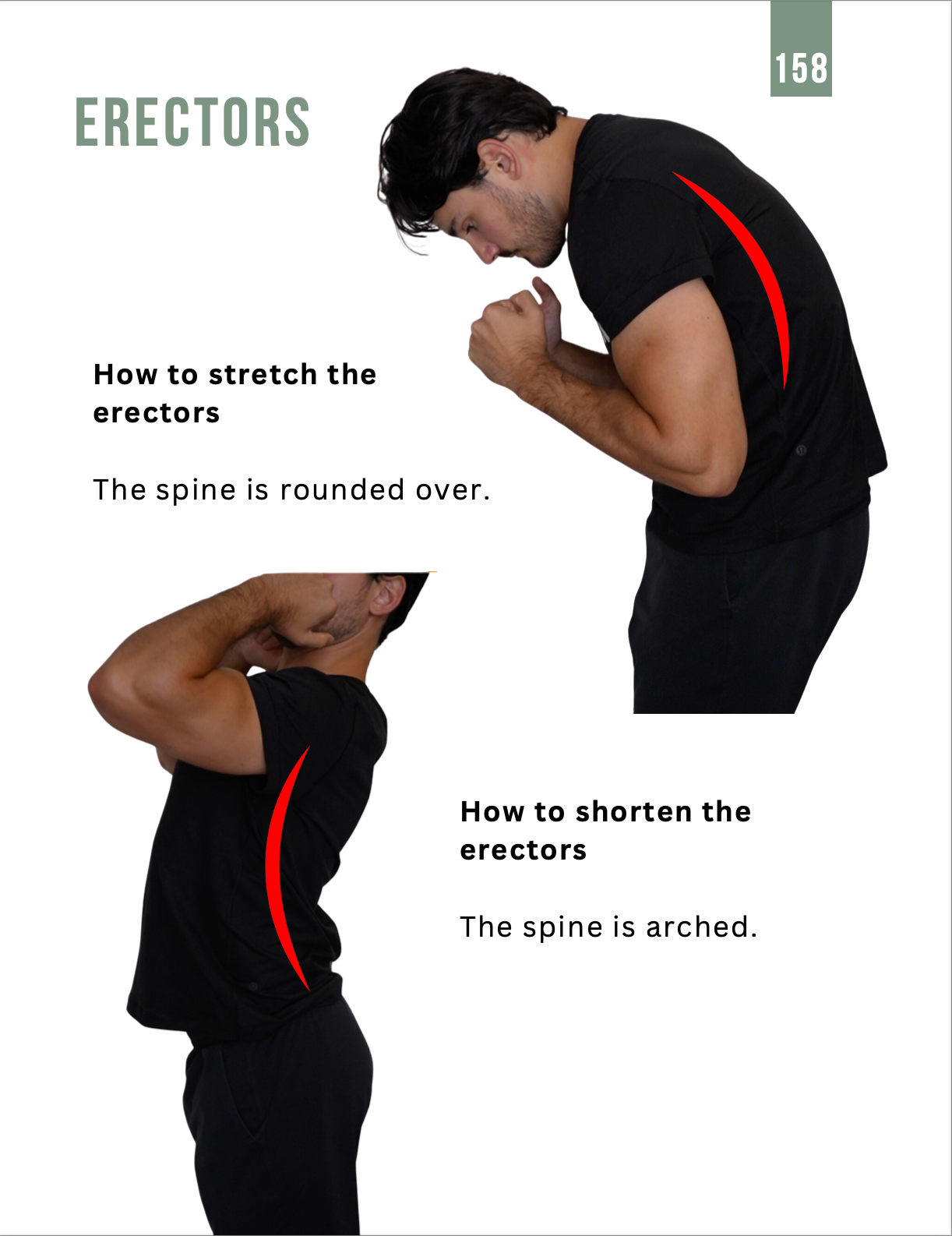

First, we need to understand how to lengthen and shorten them.

Image taken from my target any muscle guide.

Next, we need to understand how to load the body so that the erectors are required to do the most amount of work:

Image taken from my target any muscle guide.

Last, we need to understand how to stabilize the rest of the body so that the erectors can rate-limit the motion.

Imag...

How many sets should you do?

How many sets per week do you need to grow?

Everyone seems to have THE answer to this question.

"You MUST do at least 10 sets per muscle group every week."

"Actually, lower volume approaches are best. You don't need more than 5 sets a week"

"Research shows growth with up to 50 sets per week! The more, the better!"

And yet, these recommendations seem to change on a regular basis.

This week, people are all about low-volume approach.

A month ago, people said mo' volume = mo' better.

WTF?

If you want my short, non-nuanced answer to the volume recommendation question (the answer I usually give when I don't feel like asking or explaining anything), here it is:

On average, I recommend performing anywhere between 5 and 15 sets per muscle group per week.

Slightly more nuanced answer:

When discussing volume recommendations, there's one variable that a majority of people ignore.

And it's staring you right in the face.

And it's even more important than how many sets you do.

What is ...

"You Have Poor Mobility"

"You have poor mobility!"

A vast majority of you have probably been told this.

Or, you know someone who has.

Variations of this statement include:

- "You have tightness in your x muscle"

- "You have limited x rotation in y joint"

But how much sense do these claims actually make?

All of these statements use relative terminology.

If someone says that you have "poor mobility", it must be in reference to another thing.

If someone says that you have "tight" or "limited" muscles/joints, it must be in reference to something that is less tight, or less limited.

In other words...

These statements are complete nonsense.

Much of the time, people unknowingly refer to standards of range of motion.

But standards of range of motion are averages.

And people aren't average.

People are people.

Let me give a parallel.

The average height of an adult American male is 5 feet, 9 inches.

The average height of an adult Japanese male is 5 feet, 7 inches.

In this context, would it make sense t...

Seated Calf Raises Don't Grow Your Calves?

Seated Calf Raises Don't Grow Your Outer Calves

Have you heard this recently?

If you haven't, that's great.

But now you have.

Sorry.

People are making this claim now.

And like many other pseudoscientific claims, it's based on a single study, published in December 2023.

Here's the study summary:

- Population: 14 untrained participants (7 men, 7 women).

- Length: 12 weeks.

- Each subject did one exercise per leg (one leg seated calf raise, the other leg standing calf raise).

- This is known as a within-participant comparison model, and it's very helpful because it removes confounders across individuals - like lifestyle, stress, sleep etc - from results.

- The participants worked up to 5 sets of 10 reps per session, with 2 sessions per week on non-consecutive days.

- The results: the gastrocnemius (outer calves) grew substantially with the standing calf raise, but barely at all with the seated. The soleus (inner calves) muscle grew about the same in both conditions, but slight ...

Are your lower pecs sad?

Do you or your clients have trouble connecting with your lower chest?

I used to associate lower pec training with shoulder discomfort.

Whenever I would load at "decline" angles, the front of my shoulder would never cooperate.

That was...until I learned...

About the anatomy and function of the lower pecs.

The lower pecs attach from the upper arm to the ribcage.

Which means that they not only rotate the arm, like this (they are the ones in yellow):

But that they also move the entire shoulder girdle (the shoulder blade + collar bone + upper arm), like this:

In other words, the lower pecs are great at moving all three bones of the shoulder complex (the clavicle, scapula, and upper arm), not just the upper arm.

So what does this mean in practice?

For lower-pec-specific motions, we shouldn't just focus on pushing with our hands but also engage the entire shoulder girdle by pressing through the armpits.

So, rather than pressing through the hands, you can imagine pressing thro...

Understanding The Shoulder Joint

Click here to see a video version of this article (I recommend reading first and then watching).

If you like to lift weights, you've probably trained muscles that cross your shoulder joint at some point.

But you've also probably experienced pain in your shoulders while trying to do that.

Why might that be?

While we can't ever come to a single, certain answer to this question, I believe that our chances of experiencing pain in the gym are substantially lower when we gain an understanding of how the shoulder is structured and how it's naturally meant to move.

Bony Anatomy

The shoulder joint is the most mobile in the body.

To understand why this is, we need to look at the bones that comprise it:

- The clavicle

- The scapula

- The humerus

- The ribcage

The Clavicle

The clavicle is a thin, s-shaped bone that is the shoulder girdle's ONLY true joint connection to the rest of the body.

The clavicle can pivot upward, downward, forward, backward, and rotate.

Retraction = pivot backwa...